(crossposted from my lab notebook)

Yesterday my paper [cite]10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01574.x[/cite] appeared in early view in Evolution,

I didn’t set out to write this paper. I set out to write a very different paper, introducing a new phylogenetic method for continuous traits that estimates changes in evolutionary constraint. This adds even more parameters than already present in rich models multi-peak OU process, and I wanted to know if it could be justified — if there really was enough information to play the game we already had, before I went and made the situation even worse. Trying to find something rigorous enough to hang my hat on, I ended up writing this paper.

The short of it

There’s essentially three conclusions I draw from the paper.

- AIC is not a reliable way to select models.

- Certain parameters, such as \(\lambda\), a measure of “phylogenetic signal,” [cite]10.1038/44766[/cite] are going to be really hard to estimate.

- BUT as long as we simulate extensively to test model choice and parameter uncertainty, we won’t be misled by either of these. So it’s okay to drink the koolaid [cite]10.1086/660020[/cite], but drink responsibly.

A few reflections

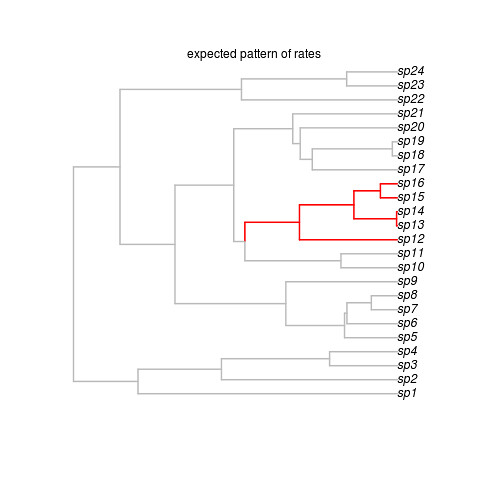

I really have two problems with AIC and other information criteria when it comes to phylogenetic methods. One is that it’s too easy to simulate data from one model, and have the information criteria choose a ridiculously over-parameterized model instead. In one example, the wrong model has a \(\Delta\)AIC of 10 points over the correct model.

But a more basic problem is that it’s just not designed for hypothesis testing — it doesn’t care how much data you have, it doesn’t give a notion of significance. If we’re ascribing biological meaning to different models as different hypotheses, we need want a measure of uncertainty.

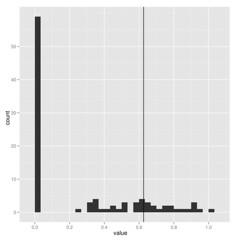

When estimating parameters that scale branch length, I think we must be cautious because these are really data-hungry, and don’t work well on small trees. Check out how few of these estimates of lambda on 100 replicate datasets hit near the correct value shown by vertical line:

The package commands are explained in more detail in the package vignette, but the idea is simple. Running the pmc comparison between two models (for the model-choice step) looks like this:

[code lang=”R”] bm_v_lambda <- pmc(geospiza.tree, geospiza.data["wingL"],"BM", "lambda", nboot=100)

[/code]

Extracting the distribution of estimates for the parameter lambda got from fitting the lambda model (B) to data made by simulating under lambda model (A):

[code lang=”R”] lambdas <- subset(bm_v_lambda["par_dists"],comparison=="BB" & parameter=="lambda")

[/code]

To view the model comparison, just plot the pmc result:

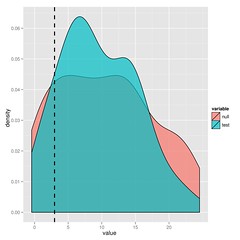

[code lang=”R”]plot(bm_v_lambda)[/code]The substantial overlap in the likelihood ratios after simulating under either model indicate that we cannot choose between BM and lambda in this case. I’ll leave the paper to explain this approach in more detail, but it’s just simulation and refitting.

You could just bootstrap the likelihoods or for nested models, look at the parameter distributions, but you get the maximum statistical power from the ratio (says Neyman-Pearson Lemma).

A technical note: mix and match formats

Many users don’t like going between ouch format and ape/phylo formats. The pmc package doesn’t care what you use, feel free to mix and match. In case the conversion tools are useful, I’ve provided functions to move your data and trees back and forth between those formats too. See format_data() to data-frames and convert() to toggle between tree formats.

Reproducible Research

The package is designed to make things easier. It comes with a vignette (written in sweave) showing just what commands to run to replicate the results from the manuscript.

This entire project has been documented in my open lab notebook from its inception. Posts prior to October 2010 can be found on my OWW notebook, the rest in my current phylogenetics notebook (here on wordpress). Of course this project is interwoven with many notes on related and more recent work.

Additional methods and feedback

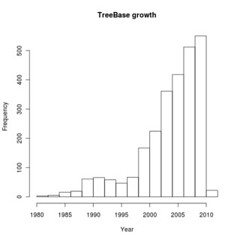

As we discuss in the paper, simulation and randomization-based methods have an established history in this field[cite]10.1371/journal.pbio.0040373[/cite], [cite]10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01025.x[/cite]. These are promising things to do, and we should do them more often, but I might make a few comments on these approaches.

We are not getting a real power test when we simulate data produced from different models whose parameters have been arbitrarily assigned, rather than estimated on the same data, lest we overestimate the power. Of course we need to have a likelihood function to be able to estimate those parameters, which is not always available.

It is also common and very useful to assign some summary statistic whose value is expected to be very different under different models of evolution, and look at it’s distribution under simulation. This is certainly valid and has ties to cutting edge approaches in ABC methods, but will be less statistically powerful than if we can calculate the likelihoods of the models directly and compare those, as we do here.

used a PGLS approach to examine patterns of body size and scale evolution in relation to latitude and climate among

used a PGLS approach to examine patterns of body size and scale evolution in relation to latitude and climate among

Recent Comments